50 years of Laser World of Photonics: A time travel into the world of photonics

2023 was a very special year for the Laser World of Photonics.

LASER 73, the very first edition of today’s leading international trade fair for photonics components, systems and applications, took place exactly 50 years ago. At that time, around 100 exhibitors came to Munich. They were pioneers of a future industry that is only just emerging. This was a mere 13 years after US researchers had been able to create the first ever laser beam. Nevertheless, Gerd vom Hoevel, Managing Director of Messe München at the time, was so impressed by the potential of this innovative technology that he launched the world’s first trade fair for lasers. Today we know just how right he was with this visionary idea. Photonics, which was in its infancy back then, has delivered on its promise to the future. It is a key technology for digitalization and the communicative networking of our modern world; it is revolutionizing medical research and practice; it enables precise insights into the worlds of nano and micro, as well as into the depths of our universe; and, in industrial manufacturing, it is constantly paving the way to even more efficiency, flexibility, precision, brilliance and sustainability. In short: The innovative potential of light as a tool that Gerd vom Hoevel recognized at the start of the 70s will last for at least another 50 years. Especially since a photonics-based future market is forming again with quantum technology. And because a good story is worth repeating, Messe München has already created an ideal platform for this key technology of the future with the World of Quantum.

But here, for once, we don’t want to take a visionary look ahead: Instead, we invite you to take a little journey with us back through time, to the year 1973.

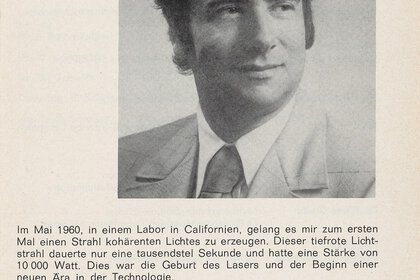

Foreword in the first catalog

The welcome address for the world’s first laser trade fair in 1973 was written by the inventor of the first laser himself. It is clear from his writings that physicist Theodore Harold Maiman long doubted the potential of the ruby crystal laser with which he produced “a beam of coherent light for the first time” in his Californian laboratory on May 16, 1960. “Deep red, a thousandth of a second short with a strength of 10,000 watts,” is how he describes the observation that is changing the world to this day. The laser, as Maiman wrote in an essay, was “a solution in search of a problem.” Today we know: That search paid off!

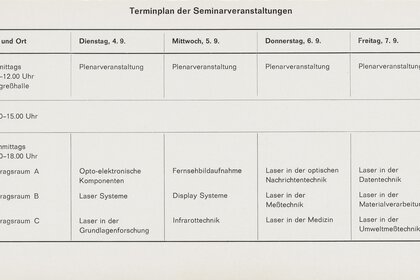

The first seminar program

In September 1973 laser technology was taking its first steps. But the seminar program of LASER 73 shows that, even just 13 years after T.H. Maiman’s successful lab experiment, there were clear ideas about fields of application for using light as a tool. The seminar titles are evidence of this visionary foresight. Because in the age of typewriters, black-and-white TVs and VW Beetles, it was nearly impossible to conceive the key role lasers would assume in data technology and in optical telecommunications, how significantly they would change medicine, measurement technology and material processing, and how much they would inspire basic research.

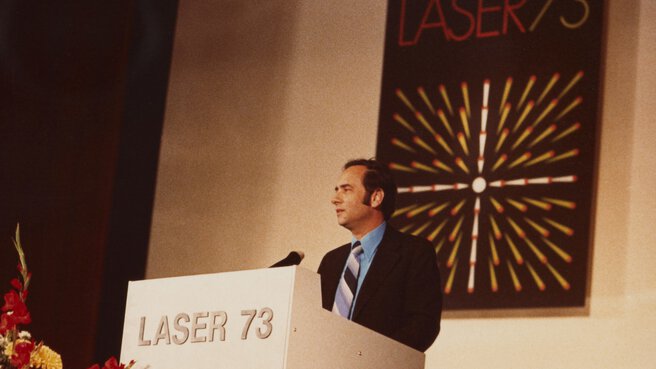

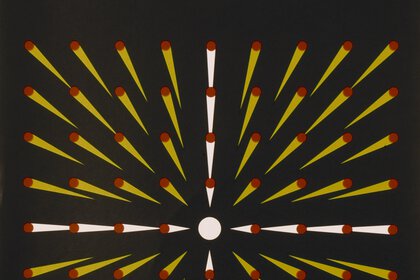

The poster for LASER 73

The LASER 73 poster is a real attention-grabber. Fine art of graphic design: three colors on a black background that clarify everything. Perfect in the golden lettering. The facts – the date, location and topic of the trade fair – stand out in bright white, picking up on the graphic logic of the logo. Red photons with a yellow light tail scatter in all directions. In contrast to their bewilderingly disordered dynamics, a white cross of light stands out, its photons radiating from the geometric center. They are focused and follow each other connected to the beam, all in the same direction. The motif seems to capture that thousandth of a second in which, 13 years prior, T.H. Maiman first succeeded in producing a coherent beam of light using a laser.

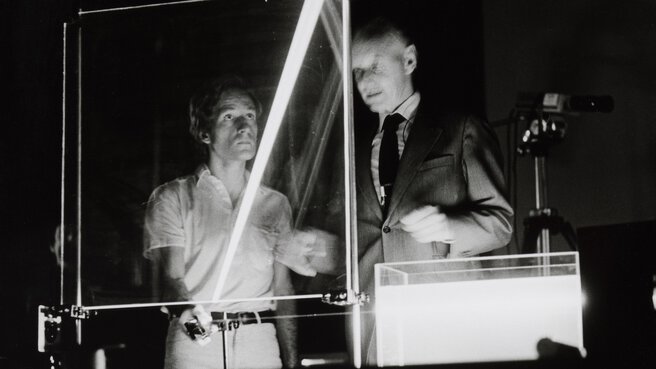

Press event for LASER 73

Who says that only opera premieres can be chic? The LASER 73 press event also called for finery. After all, over the four days of the fair, Munich played host to the international avant-garde of a completely new type of technology. On that sunny September evening in 1973, very few people realized that a future multi-billion market was about to start here, and that, within 50 years, the gamble that was LASER would become a world-leading trade fair with over 1,300 exhibitors and almost 35,000 trade visitors from 80 countries. Quite the opposite in fact: Many market watchers were skeptical as to whether a LASER trade fair was too premature.

Bavaria and LASER

In the oak wreath of the Bavaria statue in Munich, the ages merge at this moment. It’s almost as if Bavaria’s patron, erected in 1850, is holding a laser cannon in her left hand in addition to the bronze sword in her right hand. This first encounter with a coherent beam of light at the international trade fair LASER OPTO-ELEKTRONIK 1977 in Munich wasn’t to be the last. Thirty years later, a Bavarian surveying and software specialist uses laser and strip light scanners to create a digital image of the 18-meter sculpture made up of around 500 million measurement points. And a further 14 years later, the digital twin is the basis for a three-dimensional Bavaria puzzle from the 3D printer. Since then, children have been able to make a replica of the Bavaria statue on a scale of 1:15 at the Museum of Bavarian History in Regensburg.

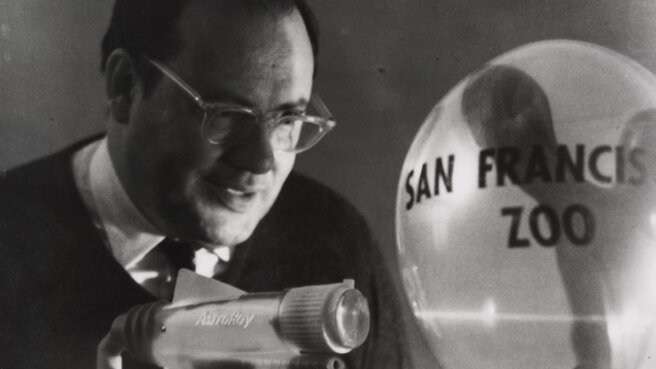

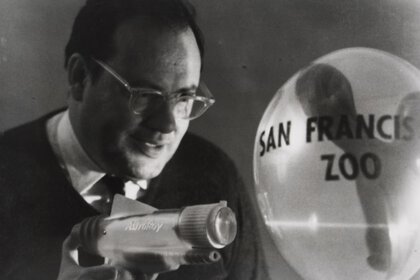

Ballon magic at LASER 77

When he presents what is at that time his spectacular experiment on his visit to LASER 77 OPTO ELEKTRONIK, the American physicist Arthur Leonard Schawlow († 1999) still has no idea that four years later, together with Nicolaas Bloembergen, he will receive the Nobel Prize for Physics for their research into laser spectroscopy. During the next decades, he will be followed by many more Nobel Prize winners who have enriched LASER and, from 2001, also the World of Photonics Congress with their lectures. But an explanation of what Schawlov’s balloon magic was about still needs to be provided: Back then, he aimed the hand laser at a balloon in a balloon and was able to remove the lettering on it without bursting either of the balloons. The experiment preempts today’s industrial laser processes: For instance, when ultrashort pulse lasers, with virtually no heat input, detach highly sensitive displays from glass plates on which the latter are built up layer by layer.

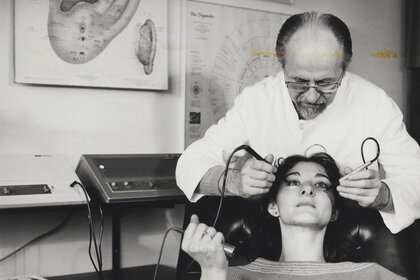

Laser acupuncture since 1973

It’s not only the premiere of the international trade fair LASER OPTO-ELEKTRONIK that falls in the year 1973. A new age also begins in traditional Chinese medicine: The doctor and researcher Prof. Friedrich Plog († 2009) uses lasers for the first time instead of needles for acupuncture. The first market-ready laser acupuncture device – the akupLaser System Plog – then comes from Ottobrunn in 1975, where Plog had developed it under the roof of the aerospace group Messerschmitt-Boelkow-Blohm. Today, painless laser acupuncture is widespread at the offices of doctors and alternative practitioners, and takes away the fear of needles for both young and old. But it’s not just a niche. After surgery had already experimented with lasers in the mid-1960s, the bundled light developed into an indispensable tool in medical research, diagnostics and therapy.

Laser welding at LASER 77

As early as the mid-1970s, the International Research & Development (IRD) Co. Ltd. from Newcastle presents a mobile laser micro-welding device aimed at ensuring safe welded joints in nuclear reactors, aircraft engines and other large-scale equipment. IRD is one of the pioneers of photonics. A full-page advertisement in the new scientist of February 1973 bears witness to that: Of the 50 topics listed that the 350 IRD engineers and scientists are working on back then, almost one in three focuses on photonics. Six projects focus on lasers. It’s about electro-optical crystals, alignment and measurement lasers, and already back then about the potential of lasers in ophthalmology and industry, whether for micro-welding and drilling, vibration measurements, or for use in mining, which calls for explosion-proof lasers. The advertisement is infused with the spirit of optimism that Messe München picked up on in the same year. With LASER, it created what is still today the ideal platform for what remains the visionary photonics community.

A guarantee for medical progress

This early presentation of laser acupuncture on a patient is only a foretaste of the impact LASER will have in the following five decades in medicine and research. Lasers are used today in highly complex and increasingly automated operations on the eye and internal organs. They are the tool of choice for removing tattoos and for many other cosmetic procedures. And in microscopy and medical imaging, in combination with artificial intelligence, they are pushing the boundaries of what is feasible. Even observing the metabolism in living cells, or looking into the neuronal processes in the brain are possible today thanks to progress in laser technology, which is why biophotonics has long since been a focus topic at LASER.

Professional Pioneers

In 1977, Spectra-Physics Inc. was just 16 years old. Founded within a year after T.H. Maiman’s lab experiment and the publication of his findings in Nature, the US start-up was the first company in the world to concentrate fully on lasers. This pioneering spirit would pay off: the Spectra-Physics team would come to LASER 77 as a global market leader for high-performance ion lasers and present “one of the most comprehensive product lines of high-quality ion lasers and accessories in the world.” With power up to 18 watts and wavelengths spanning from ultraviolet to well into the infrared range, the company advertised itself as providing one of the largest and most professional global sales and service organizations of all current laser manufacturers”.

A LASER Staple

As one of the first laser companies, Spectra-Physics earned a multi-page story in Fortune magazine in September 1969 titled “Bringing the Laser Down to Earth.” While the laser market was expected to eventually surpass the billion-dollar-per-year mark, with just 300 employees, the Silicon Valley-based start-up had already grossed 5.6 million dollars that fiscal year—one-fifth of the US market for commercial lasers. According to research by author Gene Bylinsky, there were 200 companies active in the market: 25 laser providers and the rest suppliers. Bylinsky believed they were “in the process of turning a vision of the future into an industrial mass product.” Four years later, Messe München created a trade fair platform for this young and exciting industry called LASER. Spectra-Physics has since become a staple of the event, from 1986 at LASER 2005 for its 25th anniversary to this year at LASER 2023 as a brand of MKS Instruments in Hall A3, stand 219, where it features a broad range of laser technologies for industrial, bio-medical, and research applications.

Learn more about your opportunities as an exhibitor

Be there when LASER 2025 opens its doors. We will support you with professional advice on all aspects of your trade show participation. Contact us for more information about your opportunities as an exhibitor.